Author: Ellie Schuler

Simple Gifts: One Project Indiana lineman’s family shares in his sacrifice of time and the joy in his coming home

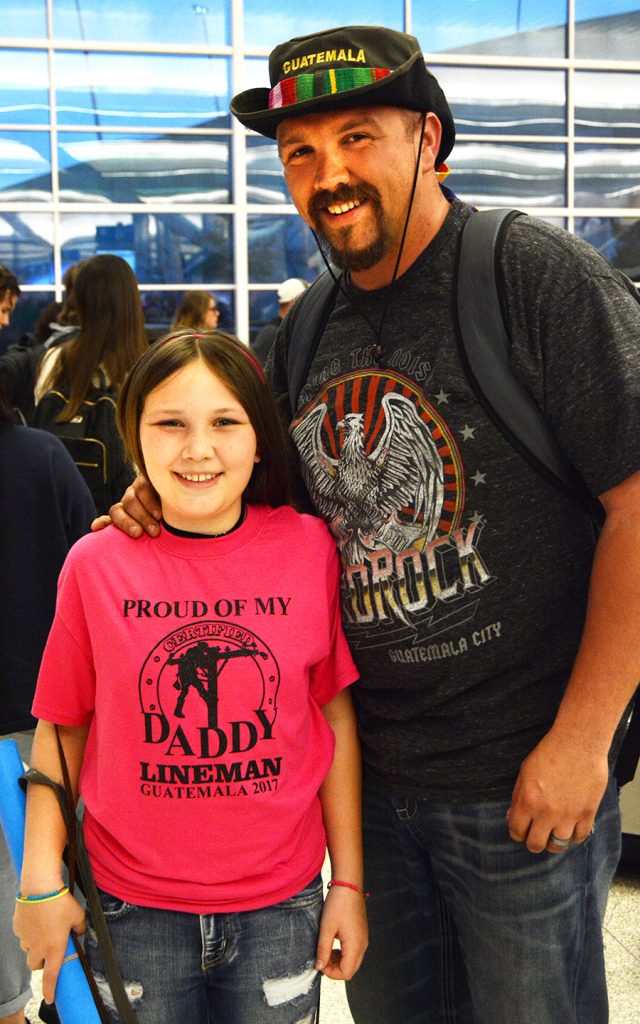

Isaac Harp missed his youngest daughter’s fifth birthday. He didn’t even call.

But it wasn’t because the Kosciusko REMC journeyman lineman forgot her birthday or was too busy to be bothered. Quite the contrary: he was another world away — in remote Guatemala on the third Project Indiana building trip in March 2017. Like the others on the trip, he literally had to climb to a nearby mountaintop to find a signal to make any brief call home. He made contact the next day with Katie, the birthday girl; his older daughter, Haley; and wife, Kelly.

Electric cooperative linemen and their families know about sacrifice. It comes with the territory: they work dark desolate stretches of rural roads during a Christmas Eve snowstorm, for instance, to restore power so others can enjoy the warm glow of holiday gatherings. But Project Indiana volunteers, working 1,800 miles from home on a Guatemalan mountainside for weeks, have faced new kinds of sacrifices to bring what Americans would consider the “simple gift” of electricity to the homes and subsistent farms of people who have never had it before. They miss birthdays and being away for two or three weeks from their wives and kids. While away, Isaac also missed out on a bout of illness that affected the whole family, including their two dogs.

The 2017 trip of “Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow” was the third of the four the non-profit cooperative initiative has made to Guatemala. Isaac joined a crew of 15 other Indiana electric cooperative lineworkers and three supervisors, supported by the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association’s international program, to electrify the village of El Zapotillo near Guatemala’s southwestern border with Mexico.

Working sometimes as high as 10,000 feet in the mountains, the team electrified 60 homes, a school, a church and a clinic with 31 miles of power line — all built by hand and without the aid of modern conveniences such as bucket trucks.

Project Indiana began in August 2012 when 28 Hoosier lineworkers spent four weeks working in the same mountainous area. In April 2015 and again in early spring of 2019, crews of 14 lineworkers battled heat and rugged terrain in the eastern part of the country. Another trip is being planned for late 2021.

Before he left, Isaac and Kelly were open with their two daughters about the “mission trip” on which he was about to embark. They celebrated Katie’s birthday early and talked about where he was going and what he would be doing.

“They understood since they’ve always seen Isaac do line work,” said Kelly. She noted they’ve seen him leave during storms in the middle of the night, and they’ve helped her take water and food to him and coworkers during extended storm-related repairs along the roadsides. “They have a good understanding of that.”

She said the girls, now 10 and 8, also understood when they explained about their dad going to an area that was remote and didn’t have electricity. “He would get the opportunity to give that to people. They understand what it’s like to have their power out.”

But to help give the girls the bigger picture, they showed them maps of where he’d be going and the terrain, and they watched the PBS documentary from the first Guatemala trip Hoosiers took in 2012 that was recorded and documented by free-lance journalist Diane Willis and a camera crew from WFYI in Indianapolis. The girls gained an understanding of the third-world environment their dad was about to venture into and the poverty he would see.

In addition, Isaac and Kelly wanted their kids to share in the upcoming experience in a personal way.

“You guys are just as much a part of this as Dad,” Kelly told Haley and Katie. “Dad’s going to be the one going, but we’re all sacrificing something so we can give to others. Part of our sacrifice is being home without him, but what are ways that we can think of giving to the people, in addition to what he’s going to be giving?”

She said Haley, then 8, immediately thought of a gift bag. Knowing Isaac’s luggage space would be limited, Kelly helped the girls gather items for two tote bags. They filled them with school supplies such as a notebook, personal items such as a toothbrush, an activity booklet, sunglasses, a baby doll or a stuffed animal, and favorite things they figured every girl their age would love: bracelets and hair ties. They also drew pictures for the two girls who would be selected to receive their simple gifts.

Once Isaac arrived in the village, locals put him in touch with two orphaned sisters, Rosita and Naomi, who were just about the same age as his own girls. He presented the totes to them. Haley and Katie wanted their gifts to go to girls their age, just so Dad wouldn’t forget his own two girls missing him back home.

The nearly three weeks away was the longest he and Kelly had been apart since they had been married. Isaac also missed out on the sickness that hit home almost as soon as he left.

Kelly said first both of their dogs got sick. Then, something moved through the family like the flu, first affecting Katie, then Haley. She noted Haley occasionally had flare ups with Gerd — Gastroesophageal reflux disease — that made the illness worse. Kelly did her best to keep Haley hydrated, using strawberry smoothies, but her stomach ailment only got worse.

As Kelly feared Haley might have to be hospitalized, good neighbors in the medical field stepped in to help her keep a close eye on the situation. “I felt God’s hands through the people that really gave to us and knew that would be a tough time having Isaac away,” she said.

The two times Isaac was able to call home while on the mountain, Kelly was vague about Haley’s illness. She said she felt they had everything they would need, and she didn’t want Isaac to worry while he was so far away. They found out later Haley was allergic to strawberries, which added to her illness.

By the time the Project Indiana crew headed home about three weeks after they left, Haley was feeling much better. Kelly and the girls drove down from Kosciusko County that day and stood outside the Indianapolis airport concourse with dozens of other family members and coworkers of the crew to celebrate the return home of the linemen.

Haley and Katie couldn’t contain their enthusiasm. “I just wanted to skip,” Haley recalled. She was giddy, eating Goldfish crackers. When her dad appeared with the other grizzled and tired linemen to the cheers of the crowd, the two girls and Kelly swarmed in on Isaac with hugs and kisses — as the other folks had done with other returning linemen.

Haley and Katie continued their joy at their dad’s return all the way through the luggage return out to the parking lot.

“There’s something about that time apart when you long so badly to be with the person,” recalled Kelly, “and then you’re able to experience all that excitement and to see how excited the girls were. It was pretty special.”

Coming home to the airport reminded Isaac of another time … when he was about the age of his daughters. “My dad went to Panama on a missionary trip. I remember going to the airport and seeing him come out of the gateway. It was kind of the same thing.”

Isaac’s dad was a contractor who used his special skill to help build a church in the Panamanian jungle. Isaac and the rest of his cohorts used their special skillset to bring electricity. “There are few people that know how to build power lines,” Kelly said. “To be able to give in that way is amazing.”

As a former electrician, Isaac used his time in Guatemala wiring the rustic homes that would soon be filled with electric light. He took three local villagers as his crew and taught them simple wiring and troubleshooting skills. Then, like most of the other Hoosiers, he left his tools for the local villagers to carry on.

Isaac’s dad later became a pastor of an independent church in northern Miami County, near Mexico, Indiana, coincidentally. And Isaac, in junior high, traveled with his parents on a church mission trip to Russia in 1998.

In addition, Kelly’s father and grandfathers were pastors of Methodist churches. Kelly also had been on mission trips to rural Kentucky and Ontario, Canada, during her youth group days. So, neither Isaac nor Kelly were strangers to what missions are all about. “But not like power lines up a mountain,” Kelly noted.

Kelly said she hopes when their girls get a little older, the entire family can take a mission trip together to help less fortunate people in Third World countries in any way they can. And she hopes the sense of compassion carried across the miles by her husband, his dad and Isaac’s cooperative coworkers can be passed on to her daughters. In the meantime, she hopes to involve the girls and even their classmates in fundraising for Project Indiana or for a need in the next village they go to.

“I feel linemen have a heart for the work that they do. It’s more than just the trade. They have a heart to be able to give truly a whole other world to people,” she continued. “It’s quite an inconvenience for us not to have power. But it’s more than that … just what it can do for countries that don’t have access to power. Your livelihood looks so different.

“For him to be able to do that — that was a big reason he went to an REMC,” Kelly added. “Part of our desire to be part of an REMC was the opportunity he could have giving back that way. It was a huge pull. Being able to join the two things he’s so passionate about — giving to others in that mission field and then his trade with the power — it was the perfect scenario.”

“We get a lot out of it,” said Isaac. “But obviously what you can give is so much more. It’s a small sacrifice for the big picture of what it can give to others. The awareness of the mission field and evangelism just by putting your feet on the ground and going out and being the hands and feet was something I always wanted to be a part of and support.”

Sharing light and hope: Project Indiana thankful for those who make electricity possible at home and abroad

In the first year of his presidency, George Washington asked the people of his nascent nation to set aside Thursday, Nov. 26, 1789, as a day devoted “to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be.”

In the midst of the bloody Civil War in 1963, President Abraham Lincoln, as he had done throughout his presidency, also asked the nation to give thanks to God for the nation’s blessings and created an official recurring Thanksgiving holiday — which, that year, also was Thursday, Nov. 26.

In this presidential election year of pandemic, racial injustice, social unrest and civil strife, Thanksgiving once again falls on Nov. 26. In spite of the difficulties we’ve experienced, Americans can still look out and realize we have been a blessed nation for which we have much to be thankful.

At Indiana’s electric cooperatives, one way thankfulness is expressed is the way it’s paid forward through Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow.

The non-profit organization was founded by Indiana Electric Cooperatives as an ongoing commitment to improve the lives of rural Guatemalans after crews of Indiana electric cooperative lineworkers spent a month in the rugged northwestern mountains of Guatemala building power lines to three villages that had never had electricity before. That first trip was in the autumn of 2012. Since then, crews have made three more trips to three other areas of rural Guatemala, in 2015, 2017 and 2019. A fifth trip is now being planned for the fall of 2021.

These trips change the linemen as much as they change the lives of the Guatemalan villagers. Linemen return home to family and coworkers speaking of the beautiful and humble villagers they meet. They have a new appreciation for what it means to be poor — as they see hardworking people living day-to-day, sustaining themselves and their families with subsistence farming, cooking in huts with packed dirt floors over open fires, and sleeping in one-room quarters. These people have so little, but they offer what they have to the American strangers who soon become friends in the two, three or four weeks the projects have taken.

Building and working on electric power lines is never easy, even in rural Indiana. Imagine working without the benefit of modern bucket trucks and power augers. Everything is built by hand from the ground up. Indiana linemen climbed steep mountain slopes and poles the old-fashioned way and strung wire across the ravines and mountainside coffee fields in misty clouds sometimes 10,000 feet above sea level, or through the heat and humidity of jungles, their trails being cleared by villagers with machetes hacking the brush away as they went.

Being a lineman is hard and dangerous. Doing this work 1,800 miles from home in the rugged areas of Guatemala makes it even harder. But Project Indiana is committed to helping these people have better lives electricity will bring. Electricity brings and will bring better health, better opportunities through new schools, better roads and a better future for the children. Truly, our linemen are the heroes. And just looking at the photos of the faces of the children and adults who received the power at any of the thanksgiving celebrations the villagers have held for crews their thankfulness is evident.

But just as with our military heroes from the Civil War to those still deployed overseas today, good deeds for others can’t be done without strong support — and prayers — from the folks on the home front. And that’s what all the linemen’s families, their cooperative co-workers, directors and their consumers have given. The “buen trabajo” (good work) for which our crews are celebrated also belongs to all who have supported Project Indiana over the years.

The thankfulness of those family members who gather at the airports to welcome the line crews home is a powerful and heartwarming homecoming every time. The children hold signs and scream. Wives shed tears of thanks-be and joy as they embrace their husbands, home safe after being gone for so long. Cooperative staff get goosebumps watching it all unfold knowing they work for something so much bigger than themselves, their own cooperative, and even the statewide and national electric cooperative associations and their member cooperatives. They are working for something that spans borders and beliefs.

Politics and policies may cloud one nation’s view of another. But the people in those rural Guatemalan villages will be forever grateful to the “Hermanos Americanos” — the “American brothers” from Indiana who gave them light — and hope for a better future.

“Now, there are people in Guatemala — just as there are in Indiana — grateful that these linemen have a passion for what they do, and that they do it so well,” noted Diane Willis, a former Indianapolis TV-news anchor, now a freelance journalist, who chronicled the first trips in 2012 and 2015. She is now a member of the Project Indiana board of directors.

“You see how hard they work for the little they have,” added Jamie Bell, a coordinator of the 2019 mission from NineStar Connect. He, too, now volunteers on the non-profit Project Indiana board. “Electricity gives them a powerful tool to better themselves — to make them want to stay there,” he said. “With it, they’ll have better health, better schools, just an all-around better way of life. I just feel as if there’d be something wrong with any of us if we didn’t want the best for people like that.”

This Thanksgiving, let’s all be grateful for our abundant blessings, like reliable electricity — for ourselves, in our homes, and that we have played a small role in helping people have better lives, too, in Guatemala.

Making connections: Project Indiana is more than just connecting power lines

In 2012, when Project Indiana first put the boots of Hoosier electric cooperative lineworkers on the ground, up the poles and into the clouds in Guatemala, it was to connect poor rural villages to electricity. And while that was a major first step in creating new hopes and dreams for the villagers, it was just the first step.

After that first trip, Project Indiana, which evolved into a non-profit organization, quickly realized that simply giving a proverbial fish to people in areas of such pervasive poverty and limited education wasn’t going to be enough nourishment to sustain prosperity. In the places where poverty has no end and wealth has no beginning, other connections were needed to help the villagers succeed.

“We are connecting them to resources, too,” said Jennifer Rufatto, former executive director of Project Indiana.

Project Indiana, along with the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, has helped start two electric cooperatives in the western mountainous areas of Guatemala where Indiana lineworkers first brought electricity in 2012 and again in 2017. A third cooperative is in a formative stage in the village in eastern Guatemala where a volunteer crew from Project Indiana was dispatched in 2015. Project Indiana’s fourth building project was in eastern Guatemala in the spring of 2019. That village joined a small utility that had been serving 12 others for about 10 years.

“They are in the process of getting their systems more developed and learning how to run an electric utility,” Rufatto noted. “They are progressing.”

As cooperatives do worldwide, following one of the seven international “cooperative principles” of business, the American electric cooperatives cooperate with other cooperatives. “Since bringing them electricity,” Rufatto added, “there is an accountability on our part to help them now grow and succeed. We have provided training and connected them with training within Guatemala.”

She noted the systemic lack of education in the rural areas makes it harder to just come in, build power lines, and move on. “So many of the people there have just a sixth-grade education, and they’re trying to work with bylaws.”

During the 2019 Project Indiana build in San Jacinto, Ron Holcomb, a Project Indiana board member and CEO at Tipmont REMC, recognized some of the issues in sustaining the utility San Jacinto was joining. He set up a short “Electric Utilities 101” course at a small church/school campus on a Saturday morning and invited community representatives that make up the electric utility — Farmer’s Development Association Las Conchas. About 35 people from the association along with interested consumers showed up on the sunny morning.

In the course of the three-hour class, slowed by the translation from English into Spanish and the Mayan dialect called Q’eqchí, which is the main language spoken in the area, Holcomb outlined how electric cooperatives work in the U.S. He noted running a utility is a capital-intensive job that requires securing financing, growing the number of consumers, and setting rates appropriate to maintain the assets and infrastructure. He also explained the need for a backup power supply in case their only generation source, a small hydroelectric generator provided by Japan’s international aid program in the late 2000s, would fail.

“Someday, we want to come to Guatemala to drink cervezas with you. We don’t want to keep coming to build power lines,” he quipped.

“Building poles and wire is just the beginning. They have to run a sustainable utility,” he said later. “But I can’t teach them what they need to know in three hours.”

Holcomb and Rufatto returned to Guatemala in November 2019 to continue training the leaders of the communities where Project Indiana had been. They also met with and established contacts with Guatemala’s president-elect and other new leaders following the country’s fall election to discuss power supply, financing, and Project Indiana’s commitment to the people of rural Guatemala.

The chief power supplier in the country, which spans the isthmus of Central America south of Mexico and is just a little over the size of the state of Ohio in area, is a government-owned and operated utility.

Rufatto noted some remarkable things are occurring, especially at the Agua Dulce cooperative which was created by folks in several small communities where lineworkers from Indiana and Arkansas built power lines in 2017.

Much like the electric cooperatives in the U.S., the cooperative leaders there realized the growth of their cooperative depends on a strong community.

“When they got together and started having conversations as an electric cooperative, they realized there are other things they need to help their village grow,” Rufatto said. “Education is a big piece of that puzzle.”

The only school in their villages taught students to sixth grade. The cooperative established a new secondary school that would take students to ninth grade. That school opened earlier this year.

From that connection, two girls from a village the cooperative served were selected to attend the World Villages for Children’s Girlstown, a boarding school in Guatemala City, that will educate them through high school. “The desire from this particular program is these students will get an education and then go back to their villages to make the village better,” Rufatto said. “That’s huge.”

In the other villages where Project Indiana has worked, progress is beginning. Around Sepamac from the 2015 build, a new road in town has been built and new stores have opened and are prospering. At San Jacinto, vented cookstoves have arrived and have been installed in kitchens to replace open fire pits in the enclosed huts. The cookstoves were encouraged by Project Indiana for all the homes it wired in 2019.

Project Indiana is beginning to plan for its next trip, which will probably be in the fall of 2021.

“We are committed to the success of the electric cooperatives in Guatemala,” Rufatto said. “It’s truly amazing and heartwarming to see Indiana’s electric cooperatives, and all the Hoosiers who support them, carry on this connection across the Gulf of Mexico to help good people make a better life for themselves in Central America.”

The first day of better days ahead for rural Guatemalans

Aura Quib Cruz sat beside the chain link fence in her front yard that ran alongside the main gravel road through San Jacinto. In the shade of a large palm tree on the western edge of her yard, she shelled the kernels from ears of corn by hand into a large plastic tub. Empty cobs piled up at her feet.

To help ease the tedious mundane task that took hours, she set up her workstation there — as if to give herself a front row seat for a historic moment in the lives of her family and fellow villagers.

Across the road in the church yard, the village green for the tiny rural eastern Guatemalan community was bustling with activity. An electric line crew from the United States had arrived earlier that afternoon, and soon, much of Cruz’s life would begin to change for the better.

The crew, 14 Indiana electric cooperative linemen and four supervisors and support staff, along with four other Guatemalans hired by Project Indiana and a Guatemalan engineer from the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, came to extend power lines some four miles to and through the village. They also wired some 90 homes, two churches and the village’s school campus.

Not only did the 30-year-old Cruz have a front row seat. Her home — shared with her husband, José; 11-year-old daughter, Dayli; and 2-year-old son, Jordan — was first to be wired.

The 2019 Project Indiana trip, which ran March 24-April 9, was the fourth and most recent for the non-profit organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives. “Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow,” in cooperation with National Electric Cooperative Association International, brings electricity to developing rural areas of Guatemala and provides the necessary knowhow the nascent utilities there need to sustain themselves and grow. By bringing electricity to rural communities in developing countries, Project Indiana provides the residents there better, healthier and fuller lives.

On this trip, the crew worked in the far northeast corner of the state (or “department”) of Alta Verapaz near its border with the department of Petén. The 2015 trip also worked in Alta Verapaz but farther to the south and west. Trips in 2012 and 2017 were in the northwestern mountainous regions of Guatemala near the southern Mexican border. Since Project Indiana put boots on the ground and up the poles and into the clouds, 70 Indiana lineworkers have now brought power to over 500 rural homes, four schools and five churches.

San Jacinto is a village of about 150 families tucked amid rolling hollows and perched along steep hillsides of knobby karst landscape. The villagers there live mostly through subsistence agriculture. They produce corn, beans, cardamom, chili, cacao (from where cocoa comes), bananas and other fruits, and raise chickens, pigs and cattle.

Watching and waiting

From her vantage point, Cruz would have seen the Indiana crew members open the doors of a barnlike warehouse on the edge of the church yard when they arrived. The barn was built to house the hardware and equipment the crew would need and serve as headquarters for the build.

Earlier in the day, José and Jordan had been among the large group of villagers gathered to peek inside at the transformers, giant spools of wire, insulators, ladders, meters and meter boxes, and other electric hardware that had been awaiting the arrival of the Hoosiers. Unlike the three previous trips, with San Jacinto, Project Indiana purchased the hardware and supplies in Guatemala, instead of having the heavy and bulky supplies expensively and slowly shipped from the United States.

All but five poles had been set, as well, ahead of the Hoosiers’ arrival. The 50 poles were set by locals and most all of the holes for the guy wire anchors were dug. Everything was done by hand.

First in line

Back across the road, José was finishing digging his own hole on the opposite side of the yard from where his wife sat with Dayli and Jordan, still shucking the corn for tortillas. He was getting ready to set the pole for his meter that would be needed the next morning. That’s when one group of the Project Indiana crew would begin individually wiring each home in preparation for when the power line overhead would be strung and dropped to his meter pole.

As Cruz sat, slowly fingering the ears, her smiling face couldn’t hide the fatigue setting in. She said it takes about 500 ears of corn to make about 100 tortillas, a staple for rural Guatemalans. She said she’ll shell that amount about twice a week. After shelling, she’ll then grind the corn into flour to bake into tortillas. While many in the village use diesel-powered motors to turn their grinders, Cruz said she still has to turn her grinder by hand. Through an interpreter, she smiled as she explained grinding takes about another hour each time and wears out both arms.

She said the first things the family plans to add once electricity arrives: an electric grinder and a refrigerator.

Toward dusk, with all the corn hulled, the meter pole set and the Project Indiana crew packing it in for the day, too, the entire Cruz family could relax. The four lined up across the seat of a small motorcycle — Jordan in front on the fuel tank, then dad at the controls, then Dayli, sandwiched between dad and mom, who was riding on the far back. And the four headed east down the road to visit friends. A new day would be dawning soon.

Memories remain from life-changing experience

Eighteen months ago, 18 Indiana electric cooperative linemen and support personnel returned home from rural Guatemala after bringing electricity to a village that had never had electricity before. It was the fourth Project Indiana trip to rural and remote Guatemala since 2012.

“Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow” is a non-profit organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives with the vision of bringing electricity to developing rural communities around the globe and providing other ongoing support for the residents there to enjoy better, healthier lives.

The March 24-April 9, 2019 trip was a life-changing trip for the villagers of San Jacinto in eastern Guatemala. But it also was for the linemen.

Linemen spend their careers literally lighting up people’s lives and working on energized line. But most would not be characterized as the “light and lively” sort or “live wires.” They work 40 feet up off the ground, or into the clouds on previous Guatemala trips, but for the most part, they are down to earth guys who are hard working and humble and, while working, are serious and professional without bravado or braggadocio.

With over a year’s time since their return, the linemen were asked to share some of their memories from the 2019 trip. Here are some reflections from three of the 14 linemen.

CLAY SMITH

Line Foreman, Whitewater Valley REMC

It has been just over a year since my return from San Jacinto, Guatemala. What an absolutely unforgettable and humbling trip that was.

To go help people thousands of miles away in another country, to get to experience the way people in remote villages in Guatemala live on a day-to-day basis, unbelievable. I am so grateful, so happy and so honored to have gotten to participate on such a fantastic mission to light up another part of the world. You simply cannot put it into words!

It was the most amazing thing I have ever done with the best group of guys that anyone could ask for.

All I want to know is: When’s the next trip? And I pray I will be a part of another Project Indiana crew in the near future. Thanks Indiana Electric Cooperatives and Whitewater Valley REMC for such a humbling and life-changing experience!

BRENT BUCKLES

Northeastern REMC

I think about my trip to Guatemala daily — from the beautiful weather and scenery to the smiling faces everywhere we went.

I remember the homes with dirt floors and handmade hammocks as beds, and the meal a mother of nine was making on a bicycle wheel over the fire.

I remember the first time meeting all of the other linemen who went, but it was as if we were lifelong friends from the start. I think about how Willy and Carlos, two young Guatemalans who left their families and friends and traveled across the country to be our translators because it was a good paying job.

I think about another man named David who rode his motorcycle an hour each way to be a teacher, and then come home to help us wire the homes in his village for electricity. And he would still be laughing and smiling the whole day!

I think about Edgar who sought me out every day to learn as much as he could about being an electrician so he could have a skill and a job once we left.

I think about all of the wonderful children laughing and following us around, peeking around the corners to see what we were doing and holding their hands in circles so we would give them candy.

If there is one thing I think of most about my trip to Guatemala it is with everything we gave the village of San Jacinto — electricity, gifts, skills, memories — I wish I could have given more!

DOUG MACLAIN

Marshall County REMC

As I ponder the significance of my part in the trip, I often land on the thought that I didn’t set or climb any poles; I didn’t string any primary wire. When I think my role in the project was minimal, I’m quickly reminded of five young men. Had it not been for my participation in this trip, they would not have learned how to wire the interior of their homes, learned how to make proper connections in light boxes or learned how to correctly connect receptacles or light switches.

Although the glory in a lineman’s world is to do the difficult things others can’t, the interior wiring was necessary.

When you have such an impact on people’s lives, it’s not hard to reflect on the times you had. Once we returned from being isolated from “the world,” if you would, you think: That is how the Guatemalans live ALL THE TIME. It’s humbling when I look back on that. Upon returning, life as we know it doesn’t change, but what comes with it is a sense of humility when you see how other people live and are happy with so much less than what we enjoy.

The thing that stands out the most to me is the friendships I made with “my guys” — the ones that went out with me every day, packed like a mule, climbing up and down the mountainous area in search of that next home to wire. The laughs we had, the conversations, however broken, and the bond that we’ll forever share.

I would love to go back and help others in Guatemala or wherever. The joy of helping others is really my driving force. The opportunity to shine God’s light through me is what I live for.

Project Indiana is a 501c3 organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives with the vision of helping developing global communities advance by adopting villages, bring them electric power and support them as they form electric cooperatives that enable them to enjoy a better way of life. Electrification projects are completed in partnership with NRECA International. To learn more about the nonprofit, visit ProjectIndiana.org.

Seeing needs; meeting needs

Water and electricity, they say, don’t mix.

The “they” who say that, fortunately, didn’t accompany Project Indiana’s 2019 trip to Guatemala.

Fourteen Indiana electric cooperative linemen and four project coordinators and support staff members spent two weeks last spring building power lines to the village of San Jacinto, and wiring homes and buildings. The day after turning on electricity in the village, they also fixed a water pumping station that had been inoperable for several months.

“I first learned they had a water source when I went down there to help plan the job in November of 2018,” said Jamie Bell, director of engineering at Greenfield-based NineStar Connect, who helped coordinate and supervise the project. “It wasn’t until after we started the actual construction on the project that we found out they had issues with the pump.”

The pump, which had been installed a few years earlier in a small pumping house beside the village’s water source, a spring-fed stream that flowed alongside the only road into town, had been out for months. A question arose about who was responsible to repair it: the village or the municipality of Chahal, which built and owned the pumping station. (The municipality is akin to county government in the United States.) So, it sat unrepaired.

The pump was electric, but its power source was the direct current of a diesel-fueled generator. In the months it had been down, the 12-volt battery for the generator engine had also disappeared.

With no pump, the villagers — mostly women and children — had to return to the ways before the pump was built: walking down to the stream to collect water emerging from the spring, and to bathe and wash their clothes amid the pools and the rocks.

“One of the Guatemalan guys with me asked if I could go down to help him with the pump,” said Joe Banfield, apprenticeship training program director with Indiana Electric Cooperatives (IEC) who also served as a project supervisor. He said the Guatemalans who speak the native Mayan language, Q’eqchi and Spanish, couldn’t understand some of the pump’s controls and instructions because they were written in English.

It was another example of the line crews seeing a need — and meeting the need.

Mixing electricity and water

“Project Indiana: Empowering Global Communities for a Better Tomorrow” is a non-profit organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives with the vision of bringing electricity to developing rural communities around the globe and providing other ongoing support for the residents there to enjoy better, healthier lives.

The March 24 – April 9, 2019 trip to San Jacinto was the Indiana electric cooperatives’ fourth trip to Guatemala.

- In August 2012, 28 Hoosier lineworkers from 17 co-ops spent four weeks working across mountainous terrain near Guatemala’s northwestern Mexican border to bring electricity to 184 homes, a church and a school in three villages.

- In April 2015, 14 lineworkers battled extreme heat and the rugged land to bring electricity to 164 homes, a school and a church in an area not far from San Jacinto.

- And, in 2017, 14 lineworkers endured temperature extremes to power 68 homes, a school, a church and a health clinic in high altitudes in western Guatemala.

The 2019 project in eastern Guatemala extended power lines into and throughout San Jacinto. The project included basic wiring of a circuit box, light sockets and outlets for some 90 homes, two churches, a school campus and the water pumping station.

In just under two weeks, they completed the building project and flipped on the circuit. With the electrical portion of the project complete, and just minor tweaks to make, they spent their last full day in San Jacinto with their attention turned toward the water works. They purchased the relatively inexpensive part needed to get the pump working and a new battery, and they fired it up. Water once again flowed from the village’s water source throughout the village via its rudimentary plumbing system of buried PVC pipes. The plumbing terminated at spigots beside the village huts and homes.

“It was still just stream water but having it pumped and available at their home had to be such a wonderful convenience. And then to lose it? These villagers displayed the patience of Job as they just quietly went about their daily lives waiting for it to be fixed,” noted Richard Biever, senior editor at IEC, who traveled with the crew.

“I cannot imagine how hard that had to be to make even one trip a day down to the stream to do laundry or collect water. And then tote the wet clothes and containers full of water back up those steep rocky hills, sometimes with two or more children in tow?” he added. “Their physical and inner strength is really inspiring.”

“I think they are used to doing whatever it takes to complete a task with their resources,” noted Bell. “They are pretty good problem solvers. Hard work never seemed to slow them down.”

Getting better

The afternoon the water started flowing again, a middle-aged woman was leaving her home with a basket of laundry on her head. She was about to begin the half mile slog down a rocky dirt road past the village school, up a hill, then down an even steeper hill to the stream. Piloting a dust-covered SUV, Hugo Arriaza, a Project Indiana contractor from Guatemala, along with two Project Indiana staffers, pulled up beside her. In Spanish, he asked her to check her water spigot. She called her daughter out from the house and Arriaza repeated his request.

The daughter ran around the back side of the home and then quickly returned, telling Arriaza and her mom the water was back on. The woman expressed thankfulness to Arriaza and the Hoosiers. She then went into the home and returned with a bag of freshly-ground cacao — cocoa — that she gave to Arriaza. It was a gift of thanks for restoring the water…saving her innumerable trips down to the stream and back.

It was just part of the long-term partnership Project Indiana is developing with the Guatemalan people.

“Now that we have brought electricity, it is more efficient to use an electric pump than a diesel engine,” said Ron Holcomb, a Project Indiana director, and CEO of Tipmont REMC who also was on the 2019 trip. Converting the pump to one using the alternating current from the power line Project Indiana ran to the pumping station is just one of the first improvements he saw to come.

“We want them to realize we’re trying to help their way of life — along with getting electricity,” said Bell. “You could say electricity just got us there. But then we found other opportunities to help their lifestyle.

“Now they have water again. And that’s just a stepping stone. It is up to them now; they have to do what it takes to make the most out of their situation,” Bell added. “From here on out, things are just going to get better and better.”

Hearts and soles

Hoosier linemen put lights in Guatemalan homes; new shoes on children’s feet

An electric cooperative lineman’s shoes are hard to fill, especially when there’s a pair of heavy metal climbing hooks attached to them. But his heart? That’s a different matter.

Each of the four Project Indiana construction trips into rural Guatemala has brought electricity to villages that never have had electricity before. Electricity was Project Indiana’s mission. But each trip has produced its own example of linemen’s giant hearts filled to overflowing with compassion. On each trip, the linemen have dug deep into their own pockets to meet additional needs they’ve recognized in the hardscrabble villages where the people have so little.

Project Indiana is a non-profit organization formed by Indiana’s electric cooperatives with the vision of bringing electricity to developing rural communities around the globe and providing other ongoing support for the residents there to enjoy better, healthier lives.

On the spring 2019 trip to San Jacinto in eastern Guatemala, the 14 Indiana electric cooperative linemen and four additional support staff members purchased about 200 pairs of shoes for children in the village. Even before the trip began, Whitewater Valley REMC, based in Liberty, Indiana, donated $1,000 toward this special trip-end ritual. It’s a service that began on the first trip in 2012.

The day after energizing the village in the green knobby karst hills, the group made a trip to a larger town to the west of where the linemen worked — to a large market. Some 200 pairs of rubbery croc-style shoes were purchased for tiny feet of the littlest kids up to larger children sizes at a shoe outlet amid an array of shops selling all types of dry goods and foods cooked right beside the crowded street. The shoes were stuffed into large yellow bags and carried back to the vehicles. The linemen also bought two piñatas and enough hard candy to fill them for the village celebration the next day.

The next morning was a holiday at school. The mid-morning celebration, planned on the grounds around the Catholic church in the center of the tiny village, would honor the Indiana crews with marimba music, Mayan dancing, incense, both the Guatemalan and American national anthems, and prayers. There would be speechifying from locals and gifts of Guatemalan flags and small tokens to the Indiana crew, games and a community pitch-in meal.

Before that, however, the linemen had one last gift to bestow — new shoes.

The linemen lined up the pairs by size, smallest to largest, on tables in a large classroom and invited the kids in in waves. It felt a little like Walmart on Black Friday. The kids rushed in excitedly. Older kids, waiting their turn outside, peeked through the windows to watch.

“The kids were so excited to get a new pair of shoes,” said Jamie Bell, a NineStar lineman who helped coordinate the 2019 trip. “I’m not sure they cared if the shoes fit or not. I feel they just wanted to have a new pair that wasn’t worn out.”

The kids would come in, some with their parents or grandparents, and sit in their tiny chairs. A lineman would size up each child’s foot and grab a pair, rip open the cellophane package with their teeth and check the fit. Even on their knees before the children, linemen would bend way down as they slipped new shoes on the tiny feet, push on the toe checking for size, and look each child in the eye. A nod and a smile meant good to go, or sometimes, a giggle told the linemen he was way off, and he’d grab another size and try again.

“We did our best to make sure the shoes gave them a little room to grow,” said Bell. “The biggest thing was seeing the joy of both kids and parents.”

After all the kids passed through, the remaining shoes were given to the school along with enough money to buy another 50 pairs for the kids who either didn’t receive the correct size or weren’t able to attend that day.

On the 2017 Project Indiana trip to the western remote highlands, the crew purchased shoes for the village children and raised money for the local school.

In 2015, in an area not far from the 2019 location, the crew purchased school supplies and raised money to support the family of an elderly patriarch in the village who had lost his sight.

In 2012, the first trip, in the western mountains near the Mexican border, the crew was moved by the story of an 8-year-old girl taking care of her epileptic father, blind mother and younger brother. The crew built the family a table from scrap lumber, purchased clothes for the family and then took up a collection that paid off what was left of the family’s mortgage — about $100 in U.S. currency but an almost insurmountable amount for the family — so the family could keep its small hut and parcel of land.“What I’ve learned about lineman after having the honor of working with them for over 30 years, is they are public servants first. It’s built into their DNA,” said Ron Holcomb, president and CEO of Tipmont REMC and a Project Indiana board member who’s been on two of the four projects. “Whether they are restoring electric service in freezing weather or providing shoes for children in lands far away, they are the heart and soul of our cooperatives.”

Clearing the Air

Project Indiana works to improve the health of rural Guatemalans

Hilaria Chub stands nearly silhouetted just inside the kitchen entryway beside her cooking stove where she is baking. A small wood fire, centered atop a piece of corrugated sheet metal, fills the dusky room with gray smoke that circles around before escaping through the door and openings in the walls just below the thatched roof.

Eyes strain trying to adjust to the glare of the sunny afternoon beyond the door outside and the darkness and the smoke inside. The stove appears to be nothing but a large box with an elevated surface about two feet up off the packed dirt floor. Ashes and charred wood cover the flat surface.

Chub, 49, then carefully clutches two corners of sheet metal, what appears to be a rusting piece of roofing maybe 3 feet wide by 4 feet long. Keeping it rigid and straight, she lifts it — woodfire and all — and slowly swings it to the right and sets it on the stove top. The action reveals what was below the large metal sheet: a large bowl with about a half dozen softball sized rolls of golden bread dough.

She picks up one loaf, gently squeezes it, and, sensing the rolls need more baking, returns it to the bowl. She then reaches over, takes the corners of the metal cradling the fire, and returns it, balancing it back on top of the bowl. She fans the smoldering fire a bit until the wood rekindles into flames.

Suddenly from behind, a small diesel-fueled engine roars to life with a burst of blue exhaust that mixes with the wood smoke. The motor drives a belt attached to a corn grinder. Chub’s 19-year-old daughter, Azucena Caal, and her niece, Elin Dalia Caal, begin pouring kernels of corn they just finished shelling by hand into the grinder’s hopper and adding water. In a pan below the grinder, they gather and roll the emerging mixture into doughy balls they’ll cook for tortillas once the bread is done baking.

This is the daily grind — literally — for the women villagers of San Jacinto, Guatemala. Project Indiana electric cooperative line crews spent over two weeks in the eastern rural village in late March-early April 2019 building power lines and bringing power to over 90 homesteads, two churches and a school campus that never had electricity before.

Unlike the three previous Project Indiana trips in 2012, 2015 and 2017, the 2019 trip brought not just electricity but also the hope for cleaner indoor air and better health. With the San Jacinto trip, Project Indiana included an agreement with the village and their electricity utility that every home the Hoosiers wired for electricity was to have a vented cooking stove installed. While the simple stoves will still burn the area’s abundant wood, a ventilation pipe would carry the smoke to the outside, clearing the air in the kitchen and living quarters of the small huts.

“We’re excited to help you bring electricity to your homes,” Project Indiana board member Ron Holcomb told San Jacinto’s residents at a town meeting the day the crew arrived, “and we’re also very excited that you are going to have stoves in your homes.”

Some 3 billion people around the world cook their food and heat their homes as they do in San Jacinto. While the smoke dissipates quickly in the open huts, the open fires have steep accumulated costs. The typical cooking fire produces about 400 cigarettes’ worth of smoke an hour, and prolonged exposure is associated with respiratory infections, eye damage, heart and lung disease, and lung cancer.

In the developing world, health problems from smoke inhalation are a significant cause of death in both children under 5 and women. Smoke from cooking activities is so dangerous it has been called “the killer in the kitchen”.

The World Health Organization reports that smoke-induced diseases are responsible for the death of 4.3 million people every year — more deaths than caused by malaria or tuberculosis — making it one of the most lethal environmental health risks worldwide. The largest burden of mortality is borne by women and young children. Among the 4.3 million who die from the consequences of smoke emission each year, 500,000 are children under the age of 5 that die due to acute respiratory infections.

Young children are particularly vulnerable for two reasons:

- They are usually with their mothers during the cooking process and thus inhale large loads of particulate emission.

- They are still growing. In comparison to adults, young children are more susceptible to these respiratory infections, leading to a high death rate in this age group. Smoke from cooking in the kitchen is one of the world’s leading causes of premature child death.

In Guatemala, proposed remedies such as locally-made, ventilated cookstoves are helping combat toxic smoke — but economics and tradition keep many people from using them. A series of studies from deep in the western highlands of Guatemala measuring the effects of improved wood-burning cookstoves on childhood health has shown the new stoves did reduce the frequency of the respiratory infections to a degree. But perhaps the most significant result of the studies showed the severity of the illnesses like pneumonia that children developed was much less in homes with ventilated stoves.

“They are suffering because of the smoke,” Holcomb said.

Holcomb emphasized the cook stoves during his talks with the villagers in San Jacinto and during a Chahal municipality council meeting Project Indiana representatives were invited to during the 2019 building project. At that meeting, Holcomb, along with trip coordinator Jamie Bell of NineStar Connect, and Hugo Arriaza, a Project Indiana contractor from Guatemala, discussed how Project Indiana, the Chahal municipality and the electric utility serving San Jacinto could cooperate on providing the stoves.

“San Jacinto will be a model community for others,” said Arriaza.

Despite the commitment from the locals in San Jacinto, progress on having the cook stoves installed has been slow.

In February, however, Arriaza reported the topic of the stoves and the commitment to Project Indiana was back on the agenda at a recent community development committee meeting. And, to encourage villagers to install the stoves (which cost about $500 in U.S. dollars each to purchase, transport and install), the new municipal government in Chahal was offering to deliver the stoves to the first 25 villagers to purchase them.

Arriaza said he expects 25 homeowners will accept the municipality’s offer and have the stoves installed in the first half of 2020, and the rest of the villagers will begin complying on a second round later this year.

“Progress in Guatemala is sometimes slower than many in the U.S. are accustomed to,” said Jennifer Rufatto, executive director of Project Indiana. “But their culture is strongly rooted in tradition. Moving away from such an entrenched part of their daily lives will take time. They are resourceful and quickly realized the benefits the electricity. Once some begin installing the vented stoves, others will see and feel the benefits of cleaner air and it will catch on.”

Sweat Equity

Guatemalans say ‘Si, si’ to helping run power lines

The lean Guatemalan wielding the machete couldn’t be missed in his cardinal red T-shirt against the thick green brush. Leading the way up a steep hillside, he quickly cleared a path for the crew of volunteers pulling the heavy electrical service line. Together, they trudged through the tall weeds and stalks of corn to the pole beside the next home in line.

Later, that same afternoon, there he was again. Now, joining others, he helped pull more line along the main gravel road from the center of San Jacinto to the farthest poles of Project Indiana’s 2019 build in east-central Guatemala. The two-week project, which electrified some 90 homes, two churches and a school, included 14 Indiana electric cooperative lineworkers and four coordinators and support staff.

Considering the day’s heat, humidity and the hills and hollows he crossed, Christsanto Tuil Caal had all the stamina you’d expect from a guy wearing that red shirt — which touted “Willmar Cross Country.”

The logoed shirt, like so many the locals wear, had come from a periodic drop of American clothing. The 35-year-old said he grabbed the shirt because he liked its image of two hands creating a “W” (which represented the high school in Willmar, Minnesota). He didn’t know the double Cs with an arrow through them stood for the endurance running sport. When asked about the shirt, he replied with a grin that he thought “CC” was just saying, “Yes, yes” … which in Spanish, it does (“si, si”).

As the old saying goes, many a truth is told in jest.

Christsanto said “yes” — multiple times — when he heard about the American lineworkers coming to extend power lines and that volunteers were needed to help. He answered the call, though he doesn’t even live in San Jacinto. Christsanto and his family live about five minutes up the line from where the electricity originally ended. He’s enjoyed electricity at his home and small coffee plantation for almost 10 years, he said.

But the father of three said he knows electricity will benefit his neighbors — especially their children. Helping do the manual work he knows how to do so well, he said, is his way to contribute. “I do it now because I’m still strong,” he said, speaking through an interpreter in his native Mayan language, Q’eqchi.

As with the previous Project Indiana trips, the work ethic of the local folks impressed and inspired the Hoosier lineworkers. Every morning, a group of men from the village gathered outside the warehouse, awaiting the arrival of the Project Indiana team from the town of Chahal where they stayed. The locals then split up with the different crews to either build power lines or wire homes. “Carrying tools, digging holes, setting poles — anything we needed, they were right there on it,” said Jamie Bell, a construction engineer from NineStar Connect, who served as a coordinator on the trip.

San Jacinto villagers already had set 50 poles before the Indiana crew arrived in March. Without the modern equipment used by lineworkers in the States, the villagers dug the 6-foot deep holes and raised each pole, weighing some 700 pounds, into place — all by hand. Another five poles were set by hand while the Indiana crew was there.

As the local crews worked side-by-side with the Indiana lineworkers, especially while wiring the thatch-roofed homes, the church and school, they’d watch intently. And the Hoosiers imparted their skills through the Spanish- and Q’eqchi-speaking interpreters or through hand motions, broken Spanish and examples if the interpreters weren’t handy.

Wiring the homes was slow at first, and there was concern that part of the project was going to take longer than planned. But over the course of the two weeks, the two groups developed a rhythm and a sense of understanding that made the work flow smoothly.

The Indiana crews wrapped up building the power lines and wiring the homes even a couple of days ahead of time. “We would not have been able to get it done without their help,” Jamie said.

Powering Up

Market owner says electricity means progress and opportunities for village

The day always started earlier for Macario Choc Cucul than for most in his little village of San Jacinto in east central Guatemala.

Every morning at daybreak, Macario left his wife, 18-year-old daughter, and 7-year-old son, and motored along the rutted gravel and rocky roads between San Jacinto and his brother’s home about a half hour away.

Macario and his family own and operate what might be considered the largest convenience store in San Jacinto. Their store, which doubles as their home, sits right by the sign that welcomes visitors along the only gravel road through town. And it’s fortuitously situated at the “T” where a dirt and rocky road takes off up over a steep hill to the village school and other homes and a church farther up. It’s a popular gathering place for the local men to visit while having a cold soda. And it’s the last or first stopping off spot for kids walking to and from school for snacks — like chips, ice cream, or a squeeze tube of frozen flavored custard or ice.

Until electricity came to the village via Project Indiana’s 2019 undertaking, just making sure he could keep the cold products cold throughout the steamy afternoons was a big part of Macario’s early morning chores.

Macario already owned two refrigerator/freezer units. But he had to keep them at his brother’s home which is in one of the 12 small towns electrified in the Las Conchas area a decade ago. So, at his brother’s home, Macario, 40, would have to load up coolers with ice, cold drinks and other cold snacks, and then drive the half hour back to his store to sell the items during the day.

Having electricity at the store will mean moving the refrigeration units on site … and so much more.

“Electricity means progress,” he said through an interpreter in the Mayan language of Q’eqchi spoken throughout the region. “It means better opportunities in the community.

“In school,” he said, “kids will have opportunities to learn about computers, have a laboratory, TV, and videos.” And he noted lights in the school will allow longer study times into the later afternoons and perhaps, at some point, air conditioning.

Macario said his family came to the Las Conchas area from Cobán, the capital of the department of Alta Verapaz, when he was in his teens. They had electricity there, he said, but he couldn’t really recall how the move affected him and his family at first. That was a quarter century ago. His father, a farmer, bought land in the Chahal municipality when larger parcels of land could no longer be purchased in Cobán. Macario’s siblings divided the land among themselves and, 18 years ago, he opened his market in San Jacinto.

Alongside the front of a thatch-roofed part of the store, stacks of crates await his next trip into the city of Chahal. There, he fills them with produce he purchases at the open market and resells in San Jacinto. His market also sells beef and chicken. Chocolate-covered bananas are also popular with youngsters, he said.

While many in San Jacinto said refrigerators would be high on their list of first appliances once electricity arrived, Macario and his family were considering a computer and a TV for the family. He said he’d like to see San Jacinto eventually build a public library, too, to make higher-tech electronics available to everyone.

With Guatemala being the number one country from which illegal immigration to the United States originates, Macario said development like electricity is key to keeping folks grounded to their home. “Some people will go away from here without electricity for better opportunities,” he said. “Now, with electricity, they will stay.”

And for electricity, he is grateful on this particular late March afternoon in 2019 to Project Indiana and its dedicated lineworkers who are building power lines throughout the town. “God will bless you,” he said for their efforts.

Better diets in the refrigerator light

It’s the middle of a hot sunny afternoon, and San Jacinto is quiet — except for the persistent crowing of a time-warped rooster across the road from the green concrete-block Catholic church, just down the hill from Macario’s place. Project Indiana lineworkers have fanned-out from the center gathering point at the church and are off building tap lines in the karst hilly landscape above the town and in both directions along the main road.

In the shade of the front porch of their home and store, Macario’s wife, Petrona, fires up propane burners beneath two deep vats filled with cooking oil. Soon, she drops breaded chicken into the boiling oil. The frying sounds like hard rain when it falls on the tin roofs overhead. Using metal tongs, she reaches into the vats, moves the pieces around and talks to passersby. She occasionally lifts a piece out for a looksee, and drops it back in.

Finally, a drumstick is ready. She grips it tightly with the tongs and bangs the metal utensil against the side of the vat to shake excess oil from the chicken and sets it on a plate. She finds another piece and places it beside the first piece. Then, she tops them with a variety of sauces from squeeze bottles and sets the plate out to entice customers to purchase the chicken as she continues cooking. Once all the pieces are fried, she moves them from the oil to a pot and shuts off the propane tank.

While electricity may not replace the propane burners anytime soon, certainly the refrigeration units on site — and in the homes of residents in San Jacinto — will aid Macario and Petrona’s efforts to sell meats and other products, and they’ll be able to offer more variety.

Just as the refrigeration that came with electrification made a huge impact on improving the diets and, along with that, the health of rural Americans in the 1930s and 1940s, it’s expected to do the same with the villagers of San Jacinto.

And, along with improved diets, there’s a simpler pleasure folks there may soon discover with electricity and appliances: The joy of treating themselves to a midnight snack of leftover fried chicken — snatched cold, straight from a plate by the refrigerator light.